| |

Purpose & Invitation

Every place, as with every person, has its own story to tell. For “A place is a story that happens many times,” as the Oregon writer Kim Stafford reminds us.

The power and beauty and tragedy of this place is palpable, its promise still to be fulfilled. This place is a story unfolding on many levels. The new story we seek to tell here is not simply the “re-telling” of history, for most of it awaits discovery.

We are called to become explorers in our own lands, to rediscover an originary map of the world, so that we may find our way home.

This site is dedicated to learning to tell the story of a place called “Cascadia.” Cascadia is a great green land on the northeast Pacific Rim. It is a land of falling waters….

Our hope is that “If we learn to tell the story of the place, then we may find our place in that story,” as the late Thomas Berry proposed. And in learning to tell the emerging story of this place, we become the story we tell.

Our interest here is both to spark the imagination and help people plant their feet back on the ground. We seek to inform and inspire the formation of a placed people who will know, love, and care, for this place as their own. We need a new story here, one that grounds us and calls people home.

So, we begin with the place and its people—with the life of the place as a whole. Always start with the land!

Come here first to learn about Cascadia, and come back to help compose a deeper story of this place. We invite your participation and contribution in helping to build the “house of Cascadia” collaboratively.

This site strives to become an original source and authoritative guide to the best of our region. The “house” of this website is in development, so check back regularly for new features….

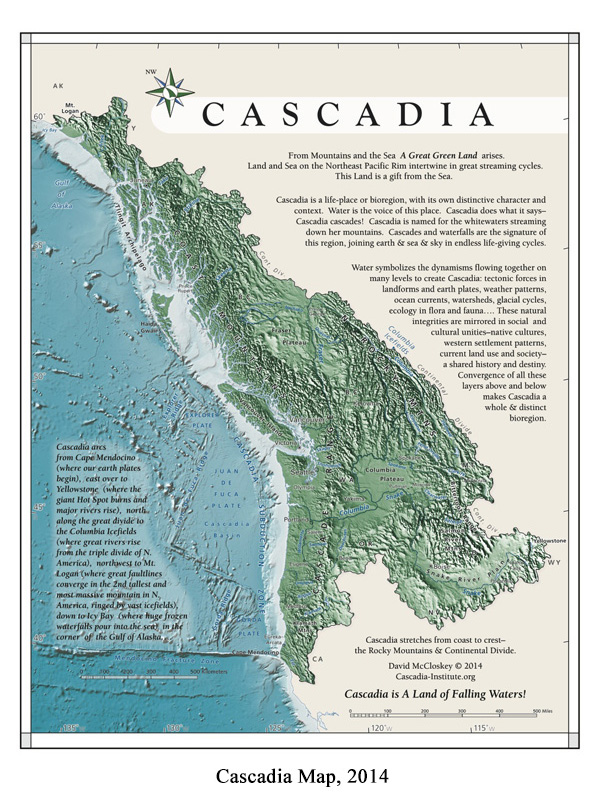

NEW!! Cascadia Map, 2015

Map of the Year debuts!

Our new “Master Map of Cascadia” has been chosen to “grace the cover of the 2015 Esri Map Book.”

(Esri.com is the world’s leading maker of GIS-mapping platforms and services). Their 30th Annual Map Book

showcases some of the best maps made in the world in the last year. Such recognition is a great honor.

This layered, information-rich, award-winning map provides a new synthesis of many different features

and layers. People will discover things they’ve never been able to see before....

For years I’ve dreamt of seeing our region as a whole. It’s taken years to get to know the land I love, thru direct immersion in the life of the larger place, as well as much research and study. But the long effort has been worth it!

Overview

The purpose of this map is to help ground people more deeply in the life of the wider place. McCloskey’s new Master Map of Cascadia shows the natural integrity of Cascadia as a whole bioregion.

Cascadia is named for the whitewaters pouring down the slopes of her mountains. Home of salmon & rivers, mountains & forests, Cascadia rises as a Great Green Land from the NE Pacific Rim.Cascadia curves from coast to crest--from the Pacific Ocean on the west, to the Rocky Mountains and Continental Divide on the east. On the seafloor Cascadia ranges from the Mendocino Fracture Zone on the south, to the Aleutian Trench in the corner of the Gulf of Alaska on the north.

In this innovative, detailed, high resolution map, viewers will see for the first time:

• The natural integrity of the whole bioregional fabric across borders (instead of cut-up political space);

• Land and Sea joined together as an inter-connected whole, showing key features of this extraordinary Seafloor in comprehensive detail;

• Cascadia in continental context--with the Sea on her westside, and the North American continent on her eastside, as well as the rivers Cascadia feeds beyond her boundaries;

• Colors--featuring Ocean Blue depths of the seafloor, Green of the living land, and light Brown of the continent, connected by the Blue thread of rivers;

• Vegetation--landscape colors representing Vegetation and Land Cover, featuring the major Forest Formations of the bioregion, with a Legend which sets a new standard.

More Info (coming)

Ordering: Maps may be ordered directly from the following website:

http://www.marshamccloskey.com/cascadiamap.html

This new small blue & green map of Cascadia, 2014, shows a real place, not an abstract nor ideal space. The life of our bioregion has been obscured, split up by boundaries and separated into categories, the matrix dismembered. This map reveals something important that has long remained invisible—namely, the integrality of the bioregion we are calling “Cascadia.” This map provides a portrait of home....

The map builds directly on the original hand drawn B &W 30” X 36” (1:3.3 million scale) map of Cascadia created by David McCloskey and published in 1988. The first map ever drawn of Cascadia, it remains the source of all map images of the Cascadia bioregion since. This presentation is a professionally drawn GIS-based map, published here for the first time.

A larger version of the Cascadia map is available as a JPEG (600KB)

This map depicts a “Great Green Land” on the North East Pacific Rim of the North American Cordillera. This map portrays the shape and boundaries of the land, as well as the lay of the land. It invites you to run your hand across the face of the land, feel its textures and depths, laminations and turnings.

This map shows, for instance, the many mountain ranges which compose this region of the Cordillera, as well as their valleys and plateaus in between. These inter-montane plateaus include the Snake River Plain as well as the Modoc Plateau, and the great Columbia, Fraser, and Stikine plateaus. The map also shows the Continental Divide--from which so many great rivers rise--which forms the eastern border of the bioregion.

The map shows the major regional river systems—Columbia, Snake, Fraser, Skeena, and Stikine--which rise from the Continental Divide, as well as many others such as the Alsek-Tatshenshini, Taku, Nechako, Quesnel, Kootenay, Pend Oreille, Spokane, Flathead, Clark Fork, Salmon, Clearwater, Deschutes, Willamette, Santiam, Umpqua, Rogue, Klamath, Eel, and in the Ish River Sound/Salish Sea country, the Snohomish and Skagit. These rivers and a thousand more form an intricate weave, animating the land, joining land and sea together....

The map shows as well the major human inhabitations in some of the main cities of the region.

Most significant is that here for the first time land and sea are shown together as integral parts of the same regional field. For here “Land & Sea ... intertwine in great streaming cycles.” After seeing the map, one wonders: how can we leave the sea off our understandings of this region, when clearly “This Land is a Gift from the Sea!”

Seafloor topography is shown in several ways: for instance, in the great Mendocino Fracture Zone, where the San Andreas Fault of California runs far out to sea, and where our own earth plates begin. Shown here are these three micro-plates with their spreading ridges—the Gorda, Juan de Fuca, and Explorer—as well as the convergent margin of the Cascadia Subduction Zone where these plates plunge under the North American plate, generating the Cascade chain. Numerous seamounts on the seafloor rise to create their own marine environments. Also shown is the shallow (@ 200 meter) depth of the continental shelf, with numerous riverine canyons cutting down thru the continental slope to the floor of the Cascadia Basin and others.

This intertwining of land and sea occurs on many levels, geologically in the long run as well as the short run in terms of the flows of winds and waters, rivers from the sky which become rainfall and runoff, glaciations, mineral and nutrient flows and cycles, seasonal upwelling, salmon runs, inhabitation of native peoples and western cultures, fishing, cuisine, etc. Mountains and forests thru their rivers feed the sea, and the sea in turn feeds the land in endless life-giving cycles. Just as studies of the atmosphere and ocean have concluded they are “coupled systems,” so, too, land and sea and sky are coupled or joined in an intimate weave in a thousand different ways. This map is meant to call out this life-giving weave!

These flowing cycles on many levels are symbolized by the many cascades and waterfalls pouring down the north Pacific slope. Cascadia sings thru her rivers! Cascades are the signature of this region. And it is this dynamism which names the place—Cascadia cascades!

Some think that our bioregion is named after the mountains—the Cascade range--and assume that the land created by these mountains is the land of Cascadia, so to speak, which is only partly true. It is true that this chain of high white volcanic peaks hovering in the sky clothed in deep forests sending whitewaters tumbling down their sides are beautiful and dramatic. But remember, there are a hundred other mountains ranges in this section of the Cordillera which act similarly. One danger is that Cascadia becomes an I-5 conceit, and that people think of their westside views as constituting the only real Cascadia, while forgetting the view of the same mountains from their eastslopes! This prejudice is reinforced among some travelers going East over I-90 or I-84 or Oregon 20 to Bend who encounter what seems to be dry barren desert, and leap to the conclusion, “This is NOT Cascadia!” But they need to open their eyes and keep going further East or North or South and they’ll discover deeper continuities....For instance, the southwest corner of Yellowstone is called “Cascade corner!”

The truth is that Cascadia is not named after a static entity like a mountain range, but rather for what the whole of the maritime mountainous region does—it cascades! So, Cascadia is named after this signature region-wide dynamism!

Others, struck by the apparent differences between the so-called “Westside”—moist, lush, green forests” vs. the “Eastside”—dry, brown, sagebrush”—maintain that there are really two separate regions here, not one. But we always need to consider the wider context and what lies beyond as well. If you go beyond the bounds of the region out onto the High Plains to the East, or the Colorado Plateau, Great Basin, or great valley of California to the south—you’ll soon know when you enter a truly different bioregion!

Consider this--all of Cascadia is part of the Cordillera—the Great Plains are not, for instance. And the land of Cascadia stretches from the coast to the crest—that is, the Rocky Mountains and the Continental Divide. The C.D. is surely a significant feature on a continental scale, and forms Cascadia’s eastern border. (Some think that the C.D. is somewhere off in the middle of the country, but may not realize that its only a long day’s drive from Vancouver, B.C, Seattle, or Portland. Similarly, while many know the B.C./Alberta provincial border, some may not recognize that this border follows that very same Continental Divide!)

The integrity of the larger region is shown in many ways, especially

in the great regional rivers—Columbia, Snake, Fraser, Skeena, Stikine—which rise from the Continental Divide, and course thru the entire fabric of the region. The arid plateaus that some think constitute separate macro- bioregions arise as volcanic inter-montane interruptions formed by similar geological processes which created the whole region. Their arid climate is not latitudinal but topographically caused—that is, they lie in the rainshadow on the leeside of mountain ranges. Hence, these areas are not true deserts but steppes, with a combination of grassland, forbs, and sagebrush, with a sprinkling of trees such as Ponderosa Pine and Lodgepole Pine, merging into foothill forests on up to the high ranges clothed in deep forests again.

Further, the integrity of the wider region is found in the same deep earth geological forces which created the various features of the Cordillera. The integrality of the region is shown in the way the winds and waters pour in great wave-trains into the interior. This integrality is shown in the vegetation which express this precipitation thru the great maritime forests of Western Red Cedar, Hemlocks, Doug Fir, etc. which are found both in the interior windward slopes as well as the Westside. Most westsiders don’t realize that there are actually two great maritime cedar and hemlock forests in Cascadia—one on the westslope and a parallel one in the interior!

And such integrality is shown in the inhabitory patterns of First Nations’ peoples—Coast and Plateau-Mountains—as well as Western settlement patterns, land-use patterns, etc. All this is part of the characteristic rhythm and regime of the larger bioregion.

A macro-bioregion such as Cascadia or California or the Great Plains has its own distinctive character and context. And a bioregional map such as the one presented here seeks to depict and evoke this particular character and context. We want to know not simply where something is located, but how the land articulates and flows, how it fits together on many levels and why, and above all, how life works here in depth....

Think of a region as a system of places—how are they woven together thru time? This weave creates a matrix or FIELD, working on many levels above and below. A bioregional map shows the woven world in depth... and invites us home....

Cascadia Institute

Cascadia Institute is a non-profit center dedicated to education about the distinctive character of the “greater Pacific Northwest” as a geographic, ecological, and cultural, region.

Located in Eugene, Oregon, the Institute is directed by Dr. David D. McCloskey. Activities include public education, research, mapping, and writing, and sponsorship of this website, as well as other forms of “thought leadership.”

May 18 – Cascadia Day

We launch this website on May 18, 2010, the thirtieth anniversary of Mt. St. Helen’s eruption. On that day people realized, forcefully, that the earth is alive!

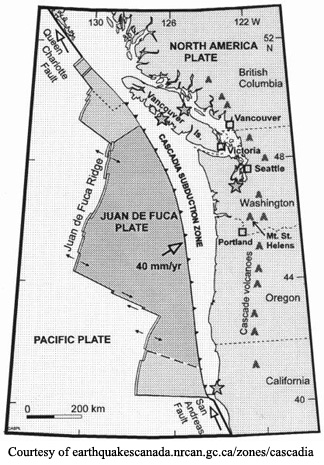

This event coincided with the emergence of Plate Tectonic theory in Geology, and discovery of what came to be called in the mid-1980’s, “The Cascadia Subduction Zone.” Massive forces that make our world—volcanic eruptions, mountain building, mega-earthquakes, huge tsunamis, among others—all came to be seen as part of the same system working deep in the bones of the earth.

Dynamisms shaping the character of our region began to be revealed for the first time.

Everything changed after that….

Welcome to Cascadia!

It's wonderful to witness the growing interest in Cascadia. When I began speaking and writing about Cascadia in wider terms in the early 1980’s, few except geologists had even heard of the idea. Through the work of many hands, thousands now speak about and identify with Cascadia. Some even call themselves “Cascadian.”

Learning to sing the song of Cascadia, we come home to honor the place.

I live in a great green land called “Cascadia.” It is a long “cool country” poured from the eastern rim of the North Pacific Ocean. Cascadia is a land all its own.

Perched high on the edge of the sea, Cascadia is a land of “Mountains & Rivers Without End” (Gary Snyder). A region where rivers are knives, and glaciers, plows. A world in which water in all its forms animates everything, inscribing a living memory into the landscape. Water is the voice of this place, calling life into the land.

When we say “land” here, we mean the life of the land taken as a whole. This bioregion is named for the white waters streaming down the north Pacific slope. Cascadia is a land of falling waters….

Cascadia is first encountered as a real place, more a living body than an image or idea. For Cascadia is a land rooted in the earth, and animated by the turnings of sea and sky, the whole mid-latitude wash of winds and waters.

As a distinct region, Cascadia arises from both natural integrities and social and cultural unities.

Everything begins with the earth, the ground we stand on. In its natural integrities, Cascadia bodies forth in a long series of linked landscapes running in belts north and south, parallel to the coastline. The deep geological processes forming this world continue today.

Cascadia, for instance, has its own “earth-plates.” Not many countries in the world have their own earth-plates, but Cascadia does. This unusual fact means that the region is anchored in the very “bones of the earth” themselves. And, one day, the story goes, these bones decided to “go dancing….”

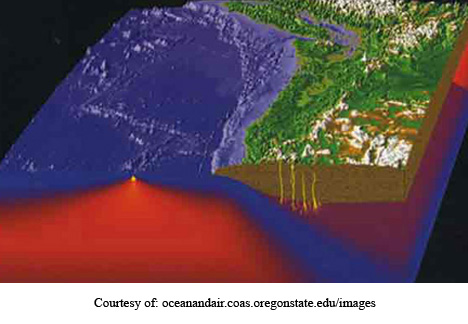

In the dance which becomes Cascadia, the North American continent overrides a conjunction of the Pacific plate and Cascadia “micro-plates.” This slow, hidden, tangled, dance is performed along “transform faults,” generating what geologists in their own earth poetry call “collisional orogenies.” (“Orogeny” means mountain-building, and “collisional” means earth-plates smashing into one another).

This dragon-dance deep in the bones of the living earth is the fundamental and continuing cause of our landscapes. Cascadia is first a verb before it condenses into a noun; a performance or phenomena that generates a form. If you treat Cascadia merely as a static “object,” then its dynamism—the dance—will blow right past you. For the world is first danced into being….

And, oh! how those “bones can dance….” Our “Cascadia plate” dives twenty miles and more under the edge of North America into the “Cascadia Subduction Zone,” running for almost 700 miles from northern California (where the San Andreas fault veers out to sea) to the northern tip of Vancouver Island. There it joins the Queen Charlotte Fault and its successors jamming north into the corner of the Gulf of Alaska. Finally, these converging forces reach the apex of Cascadia, the towering massif of Mt. Logan, where the bones of the earth pivot again.

Dance—bones--body. On this foundation, Cascadia rises in a similar integrity of form that pervades all the other natural systems in the region. Given its unique topography and location, Cascadia has its own distinct climatic regimes, ocean currents, and river systems. The dynamic character of this land expresses itself on many levels.

Cascadia is blessed, above all, with “ten thousand” streams and powerful rivers. Everything flows and cascades here. The circulation patterns in this flow naturally articulate themselves in watersheds. In Cascadia, “a river runs through us….”

Bones—blood—breath—skin. Sunlight and seabreeze breathe life into the land, enflesh the body of the world.

Said another way, based on this physical template of topography, climatology, and hydrology, distinct life-forms and ecological processes emerge. Cascadia enjoys its own special flora and fauna, its own ecological history as an unfolding matrix of life, and, we trust, its own evolutionary potential.

Vast belts of evergreen forests and salmon swimming through them from mountains to the sea stand forth as the totems of Cascadia.

In its human unities, due to its diverse, densely-packed, and naturally abundant landscapes, Cascadia once had a rich variety of highly distinctive “Coast and Plateau” peoples. The inhabitations of these “First Nations” constituted some of the most densely populated areas of native North America. Their continued presence here deepensrecognition and celebration of “the spirit-in-the-land.”

Cascadia has also seen similar western settlement patterns: exploration by sea and land, locational patterns along rivers and ports, demographic patterns in population concentration in favorable areas, etc.

Today, Cascadia has a shared regional economy, resource base, transportation, communication, and utilities systems, common land-use patterns and conflicts, etc., as well as cultural attitudes and emerging values; in short, a shared history and destiny.

In sum, it’s not the case that Cascadia can mean almost anything, as some suggest, nor that “defining a region is nearly an impossible task,” as others maintain. For a shared dynamic unity of formation is the decisive factor in generating the distinctive character and boundaries of a bioregion. The key is how the dance unfolds….

A few years back, I was out for a run around our hill when a man, watering his lawn, yelled out to me: “What are you running after? Why do you all run so?” I stopped, and answered him, “I run to make the trees grow, for the world and me, we breathe together.” A bemused smile blossomed on his face, “OK,” he said, “That’s it. Finally got an answer.” So we waved, agreed upon our reason for being here, and I set off again, breathing in the warm sunlight of a summer afternoon….

Well, that is it, isn’t it? When we drink her waters, for instance, Cascadia flows through us--both inside and outside at the same time. The river of the world flows through a river in the mind, and we ride that current home. Our bodies—world and self—join in the most intimate ways.

Similarly, in starting our explorations with the land, we want to find a place where the body of the land and perception join. The land we seek to understand is both “a physical terrain and a terrain of consciousness.” In discovering the dance of the place, we hope that the life of the land forms a living image in our minds and hearts.

Cascadia reveals her character in what she does. So, we begin with the land by attending closely to how it presents itself in its Shape, Location, Size, Face, Lineation, Population, and Field as matrix of life, as well as its Boundaries.

If you look to the southwest on the third or fourth night of a new moon, you may see the face of Cascadia shining in the sky. For Cascadia is shaped like the top-half of a quarter-crescent moon rising.

Cascadia is a great green curving land, turning round between sea and land and sky. Everything moves here, nothing stands still, even “the blue mountains go walking.” Cascadia arcs on all sides, the form moving through curved space makes.

Cascadia is the shape of a curling wave, a full sail, an orca fin. Each finds its own flaring form flowing through liquid oceans of air and water.

Cascadia is more a dance than a fixed space, a great long-looping, syncopated dance, the form music traces in the air, the shape a wild Irish slip-jig carves out in 9/8 time.

In this flying arc of landscapes, you can feel tremendous forces working, a tension or torque in the sky above and earth below, a curve of binding energy revealed in the very shape of Cascadia itself.

Orientation

Getting the orientation of Cascadia right is important. Some tilt it over to the right so its outline fits easier on a page, but that’s disorienting. For everything turns left here....

Now, the coastlines of Oregon and Washington, despite their own curves, basically stand straight up, that is, trend north. However, the bones of this earth shift alignment north of the San Juan Islands on the boundary line in the heart of the Salish Sea. Therefore, on a boat heading up “The Inside Passage” toward Alaska, you need to set your compass bearing on 310 degrees heading west/northwest.

If, on the other hand, you key to the 125th parallel of longitude and proceed north along that line, you would end up in the Beaufort Sea off the Northwest Territories of Canada; in the Arctic, not the Pacific.

On a boat you need to thread your way through the mazeway of channels and islands over toward the west—“keep heading west!” you remind yourself—to reach142 degrees, 17 more degrees of west longitude than on the southern coastline.

Cascadia curves and recurves upon itself, a spiral edge along the sea, always trending northwest. It’s the place a long looping dance makes…..

Where in the world is Cascadia?

You won’t find its location on most maps yet, for its still a dream image of a real place. Insofar as the idea has percolated into common consciousness, Cascadia is thought to be the northwestern margin of the United States. Its real location, nature, and boundaries, however, remain unclear.

Cascadia’s location may be seen from at least two different perspectives. From the perspective of the ocean, Cascadia is located on the northeast Pacific Rim; it's the eastern shore between Alaska and California. From the perspective of land, Cascadia is located on the far northwestern corner of the North American continent.

Northeast/Northwest—Rim/Continent—two directions, one place. Therein lies the key to Cascadia’s location.

Now, you could also say that the region is a zone between 110 degrees and 140 degrees west longitude, and between 40 and 60 degrees north latitude. This position on the global grid is useful in a number of ways. Now, you could also say that the region is a zone between 110 degrees and 140 degrees west longitude, and between 40 and 60 degrees north latitude. This position on the global grid is useful in a number of ways.

Or, starting from its position on the far northwestern corner, you could emphasize the distance of the region from older population centers on the East Coast, and how it’s separated by a vast continent and two oceans from the rest of the world.This response emphasizes isolation. Or, you could say that Cascadia comprises the states of Oregon, Washington, Idaho, northwestern California, Montana west of the Great Divide, as well as most of the Canadian province of British Columbia, and all of southeastern Alaska, with slivers of Nevada, Wyoming, and Yukon thrown in for good measure. This tells political location; add roads, counties, etc., and you have the standard map package.

Dis-Orientations

But, consider that latitude/longitude points, isolation from distant centers, and lines on a political map, don’t actually tell us much about Cascadia as a location. They all approach the region from the outside, while the inside seems empty. From such standard perspectives everything is already known—“ho hum, there’s nothing new to discover”—pat answers that have forgotten their own questions.

Mathematical coordinates dropping down from the skynet, geographical distance from other starting points, lines on a geopolitical map—all these and more may describe spatial position, but tell us very little about the locus of the place itself.

Read More...

Area

As noted earlier, Cascadia comprises the states of Oregon, Washington, Idaho, northwestern California, Montana west of the Great Divide, about four-fifths of British Columbia, and Southeast Alaska, taken as a whole.

Cascadia contains over 600,000 square miles of land; counting the water and sea area would add considerably more.

Note that this number measures area at a medium-scale. However, because of the steep relief, densely packed topography, curving contours and angled planes, all colliding like a cubist painting, a fine-scale of resolution may enlarge the total surface area considerably.

Distance on Sides

On its southern side, as the crow flies from Cape Mendocino in northern California over to Yellowstone Lake, Cascadia covers about 800 miles.

On its western leg, as the crow flies Cascadia runs north up the coastline about 1,700 miles from Cape Mendocino to Mt. Logan in Kluane National Park in the Yukon.

Hence, Cascadia is twice as long as it is wide.

On its third side—the eastern border—Cascadia runs along the rugged ridgeline of the continent on the “Great Divide,” floating as a kind of hypothetical hypotenuse, a ragged line wandering all over the landscape like a drunken surveyor. It does form much of the border between Alberta and British Columbia, so it’s well-known to that extent. But, like surface area or coastline, its length on the ground seems infinitely extensible, and so, for now, I prefer keeping it indefinite, something of a mystery, a horizon more to be imagined than grasped.

Together, these three sides form a left-leaning triangle wedged in between the northeast Pacific and the northwest corner of North America, a flying arc of landscapes called “Cascadia.”

Read More...

Landscape is the face of the place, how its history and character shine through. Landscape registers the story of its own formation. It expresses all the energies flowing through and animating this world, throwing its contours into dramatic relief.

Cascadia is a deep furrowed land poured from the North Pacific, flowing from the ocean depths in wave upon wave crashing on the shore, cresting up to the heights of the Rocky Mountains. From their backside in Montana, for instance, you can see how the Rockies themselves are cresting waves breaking upon the shore of the North American continent.

In the North Pacific, where mountains meet the sea, you find a relentlessly dramatic landscape, one of the freshest, most diverse places on earth. It all begins in the sea, mother of the winds and waters, mother of the mountains and land, mother of us all.

First, there is the ocean whose eternal rhythms, storm-tossed depths, and upwelling zones, create rich habitats over the continental shelf.

But there’s another world hidden below its surface. Off-shore several hundred miles, underwater, on the seafloor, rise deep-sea volcanoes, and red-hot spreading rift-zones spilling lava in magnetic stripes down either side, filled with unique sulfurous life-forms unknown a few decades ago. Here earth-plates slip-slide past one another, crashing together, slamming mountains straight-up out of the sea.

The same seafloor contains broad basins and deep submarine channels, as well as estuarine fans and  deltas, and sedimentary aprons. Here you find the plunging trench of the Cascadia Subduction Zone, source of mega-thrust earthquakes, massive tsunamis, and mountain ranges. Thirty years ago no one had ever heard of the Cascadia Subduction Zone, but now its shaking has changed the very face of our region, again. deltas, and sedimentary aprons. Here you find the plunging trench of the Cascadia Subduction Zone, source of mega-thrust earthquakes, massive tsunamis, and mountain ranges. Thirty years ago no one had ever heard of the Cascadia Subduction Zone, but now its shaking has changed the very face of our region, again.

The Cascadia Subduction Zone is covered by a blanket

of sediments. It is flanked landward by a sedimentary wedge on the apron of the continent forced up by subduction, a slow-moving slab of slices cupping upwards, and tipping like a cresting wave rolling over the edge of the land. It’s destined to become our next coast range.

All this complex, taken together, deserves to be called “The Cascadia Sea.”

Read More...

If you run your hand across this land, you can feel its raised grain on the rough surface. This grain rises and falls in a distinct pattern.

The deep-furrowed and laminated landscape of Cascadia has its own characteristic grain or lineation. Like a giant tree split open, the fibers of the land’s body lay down all in one direction—to the north, or rather, slant from northwest to southeast. The land is grooved along this grain. Everything naturally flows north and south along the grooved grain, while going east and west against the grain is hard.

The lay of this land is controlled by belts of mountains-and-valleys which make up the Cordillera, or “corded rope” of mountain ranges trending northwest. The Cordillera parallels the coastline along the “Ring of Fire.” And since this coast runs north/northwest, so, too, does the corrugated landscape pushed up from the sea, and plastered onto the continental margin. Deep tectonic forces control the lay of the land here.

This lineation of the land along mountain belts parallel to the coastline gives rise to the distinctive rhythm of Cascadia seen in its succession of coast, mountains, interior valleys and inland seas, mountains, plateaus, and mountains, running west to east. Indeed, the mountain-valley-plateau pattern creates a distinctive regime here.

Axes

In essence, the two great axes of the region are coast and mountains. Coast and crest diverge widely on the southern side of Cascadia, with the full symphony of coast-mountains-valleys-mountains-plateau-mountains-and more mountains rising to the Continental Divide. Proceeding north along the grain of the land, this constellation of interior landscapes begins to shrink. At its crescendo in southeast Alaska, coast and crest converge until everything in between is squeezed out, leaving only huge towering mountains plunging directly into the sea, calving glaciers into tidewater.

In glaciations, the icesheets pulsed north and south along these axes. Flora and fauna flowed back and forth, north and south, in these glaciations and retreats.

In Seattle, for instance, the glaciers left their distinctive mark on the land. Seattle stands forth as a city of hills, perhaps fifty in all, and the hills rise as long graceful flaring and fluted “drumlins” formed as “recessional deposits” as the glaciers waned. The lakes and sound are glacial troughs gouged out by meltwater rivers inside the ice cascading under and through the glaciers.

As a result, the hills and lakes and sound all trend north and south. Since highways are aligned with this lineation, traveling north and south through the Puget Sound area is relatively easy. But moving against the grain of the land east or west is a challenge. You have to thread your way through narrow gaps, around hills and lakes, through a thousand chokepoints, in Seattle’s famous “hour-glass shape.” Blame the glaciers if you don’t like the traffic!

Moving Against the Grain

These two axes dominate the landscape. Moving across these axes, and thus against the grain of the land they form from west to east, is often difficult because you encounter all the roughness of the landscape in between coast and crest. It means clambering endlessly up and down and over and around and through the tough wild terrain of hills and mountains and plateaus and deep gorges and more rugged plateaus and more ragged mountains thrown up by tectonic forces. Instead of traveling a hundred miles, it feels like a thousand.

You encounter an incredibly rugged and diverse series of landscapes packed into short distances moving over a sub-regional divide like the Cascade Range. With difficulty you enter one world and quickly pass into another, and then another, in short order. Passage across the grain of the land becomes almost bewildering in its complexity.

Read More..

About 17,000,000 people live in Cascadia in 2010.

Despite, or perhaps because, of the vast scale of the rugged land, population has never been widely scattered, but rather concentrated in favorable areas. In the old heart of Oregon, for instance, in 1860 74% of the population was concentrated in the Willamette Valley. This settlement pattern largely reflected the Donation Land Act claims, and established a pattern that persisted.

A century later in 1960, despite some fluctuations, 66% of Oregon’s population still concentrated in the Willamette Valley. Fifty years later still, it had risen to 70%. Thus, for a century and a half, about seven in ten Oregonians have lived in the Willamette Valley.

A similar pattern plays out in the Puget Sound/Salish Sea, where 65% of Washington state’s population lived in 2009.

A similar pattern plays out in the greater Vancouver-Victoria, B.C. area, where 60% of the provincial population lived in 2009.

An even more dramatic instance of the same pattern is found in Idaho, where 73.5% of the state’s population lived along the Snake River Plain in 2009.

In fact, over 68% of Cascadia’s population lives in these four areas alone. (Willamette Valley=15.8% of the total regional population, Puget Sound = 25.5% , Strait of Georgia = 20.2%, and the Snake River Plain = 6.6%).

More specifically, the region’s population is densely concentrated in metropolitan areas. In 2009 43% of Oregon’s population concentrated in the tri-met area of Greater Portland (Multnomah, Washington, & Clackamas counties).

In Washington 51% of the state’s population concentrated in the Greater Seattle area (King, Pierce, & Snohomish counties) in 2009.

In British Columbia 52% of the provincial population concentrated in the Greater Vancouver Regional District in 2009.

Linking population to geography gives an even more dramatic view of density,

Stated cumulatively, 45% of the total regional population lives in three core metroplexes (Greater Seattle, Vancouver, B.C., and Portland, ranging upwards of 2,000,000 people), living on only 1.7% of the total land area of the region.

Adding the next three largest metro areas (ranging from 350,000-700,000 people) to the running total, 54% of the regional population lives in six metro areas, cumulatively, on about 2.5% of the land base.

Adding in the next six largest metro areas (ranging from 200,000 to 350,000 people), 71.6% of the total regional population lives in twelve metro areas, on only about 4.5% of the land base.

Finally, adding in the next largest metro areas (ranging from 100,000 to 200,000 people), 81% of the population in the twenty-three largest metro areas lives on about 8.8% of the land base.

It is remarkable, in a region of over 600,000 square miles, that there are only twenty-three metro areas larger than 100,000 population. And, even more remarkable that over 80% of the people live on less than 10% of the land.

Further, of the 171 total counties, regional districts, and boroughs, in the region, 29 contain 4/5ths of the population; in other words, only 17% of the administrative districts contain more than 80% of the population.

The imprint of the land remains strong on these population centers. Thus, the linkage of demography to physical geography is also significant, for population centers founded in earlier centuries are almost all located on rivers or rivers and seaports.

Coming Later

Description

Where does Cascadia begin and end?

Cascadia is a curved land running from coast to crest—from the Pacific Ocean on its west to the Rocky Mountains and Continental Divide on its east.

On its western side, Cascadia runs northward along the coastline from Cape Mendocino in northern California up to around Icy Bay in the corner of the Gulf of Alaska.

On its southern side, Cascadia runs from the Eel River drainage in the North Coast Ranges up to Mt. Shasta and along the Modoc Plateau in northern California, then eastward around the border of the Great Basin into central Oregon, through northern Nevada and Utah, to the Grand Tetons and Yellowstone National Parks in Wyoming, on the Great Divide.

On its long eastern side slanting to the northwest, Cascadia follows the Continental Divide north from Yellowstone through Montana up along the spine of the Canadian Rockies through its magnificent National Parks. Here the Great Divide also forms the boundary between the provinces of British Columbia and Alberta. The boundary of Cascadia then follows the Great Divide northwest over to the boundary ranges between B.C. and Alaska, up to massive Mt. Logan in the spectacular Kluane-St. Elias National Parks, then loops back down to meet the coastline west of Icy Bay, near the border of southeast Alaska.

Discussion and Delineation

People always seem to want to know: “Am I in or out of your bioregion? Where are the boundaries? And, why draw the boundary here rather than there?”

The simple, “nutshell” version above is useful in some ways. But it doesn’t address, of course, the actual location of Cascadia’s boundaries “on the ground.” We need to become far more specific to know where to look. Moreover, the questions of the nature and location of boundaries are thorny issues, with profound implications. Here we only begin the reflection.

One fact seems clear at the outset: We need to be able to say where something significant begins and ends, opens and closes. That is the very nature and function of borders and boundaries. But, how to discover boundaries, what boundaries are and do, and how and where to designate them, present interesting challenges. We also need insight into the process involved in discovering boundaries.

Read More...

Having looked into Cascadia’s character from the inside, as it were, we turn to consider its context from the outside.

Context means how things are “woven” together as parts of a whole fabric, or fit together as parts of the same body. In getting the big picture here, we can look for the context-forming integrities of the larger body of the land in several ways.

Regions of the West

In terms of the Pacific side of the Continental Divide, for instance, Cascadia stands forth as one of the five great regions of western North America. It’s the Pacific slope north of the Great Valley of California, northwest of the high red rocks of the Colorado Plateau, the land north of the heart-shaped Great Basin sandwiched in between the other two, having no outlet to the sea, as well as the land far to the north of the low deserts of Sonora, and related regions to the south into Mexico.

In its wider continental context, we can explore Cascadia’s location in terms of its relation with contiguous bioregions, and then its role in relation to the whole continent.

“Mapping the Body”

Before looking into Cascadia’s neighbors, it might help to explore what “mapping the body of the land by contiguity” means.

To find the centers and edges of a world is a great quest. You begin at home, of course, exploring every “nook and cranny” of your own backyard, and probing the edges of your local neighborhood. Emboldened by the knowledge, and growing comfortable with dwelling in a wider backyard, you decide one day to go “down the road,” “around the bend,” and “over the hill” to “see what you can see,” to find out “what’s happening there.” “Sweeping out the territory” in this manner, bit by bit you build up a larger map of how the world is put together. Backyard, neighborhood, settlement, watershed, and beyond, each place is both home-base and stepping-stone in turn. This is the naturally human way of coming to know your wider place in the world.

And in going to the other side, like passing over the Cascade crest down its eastside, your horizons widen considerably. When moving into another ecoregion different than your own, you discover the astounding power and diversity of the land. It’s a “world of wonders.” Curiosity enlivens and enlargens the imagination, and the complexly articulated body of the bioregion begins to emerge.

Read More...

Back to the top...

|

|