| |

This is the natural process of “mapping by contiguity,” that is, composing a living image of the body of the world. This step-by-step process of discovery by linking one place to another, and then those, in turn, to a third place, each time weaving them all together as parts of the same body, generates understanding of how the whole is composed.

It gives a different perspective, for instance, than that gained in the “spot consciousness” of parachuting in and out of places on airplanes. For then you have no real idea of how you got there, of how the place you left from or are going to connects part by part to where you are. There is nothing in between but airspace, leaving you lost in jet-lagged disorientation.

The god’s eye-view from space in satellite photos, as beautiful as it can be, is similar in some ways, for you still have to “geo-reference” every point, that is, tie it to a known location on the ground. And every map needs to be “ground-truthed.”

Back on the ground, when you probe further out beyond the known, and incorporate each new valley or basin or city or mountain range into a deeper body, like arms and legs extending, and comprehend this body in an image in your head called a map, then the world begins to make sense as an organic, integral, living whole. Finally, you may begin to assemble a meaningful map of the world, fitting the pieces together as parts of a wider whole. This is what the bioregional method of mapping by contiguity means--to find and create wider, deeper contexts, as you “weave” the deeper integrities in the body of the land together.

Recall earlier when we urged the traveler going over Snoqualmie Pass to “Keep Going,” to go beyond the other side of familiar home in the Seattle area, to discover what’s “going on out there,” and how it connects to home. And then keep going to the other side of the other side, where wonders wait….

And if you “Keep Going” in this manner, eventually you’ll come one day to the edges of your bioregion (see “Boundaries” section). Edges are inherently dramatic, lively places.

And beyond the edges of Cascadia, you enter radically different “worlds”—bioregions with very different “characters and contexts.” In each case, what makes bioregions distinctive is the combination of their unique “characters and contexts” taken together.

Though standard geographies tell us about “this zone and that one,” as if they were infinitely repeatable around the globe, none of the bioregions surrounding Cascadia occupies the same zone, for none of them have the same contextual location to the others. Because the ways in which the larger body of the land joins parts and articulates wholes are different, there will be different flows across the land, and, thus, different ecological profiles.

Cascadia’s Neighbors in the West

Lacing up our “Seven-League Boots,” for a wide-striding, whirlwind tour, we visit our neighbors proceeding around Cascadia in a counter-clockwise circum-ambulation.

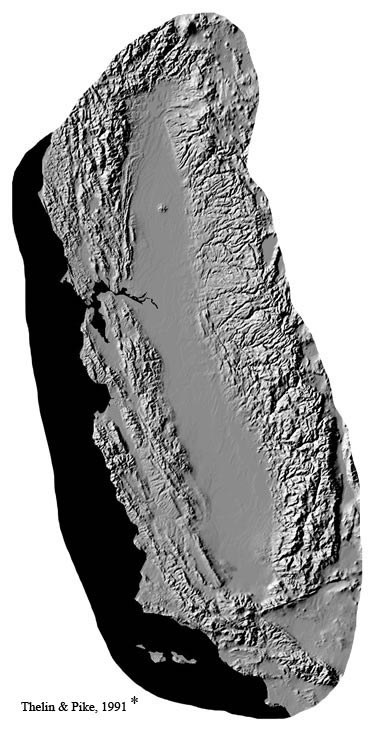

California

Starting along the coast on the southern border of Cascadia, passing through the shining gate of Mt. Shasta, you enter the golden bowl of the “Great Valley” of California. Like two hands cupped together, water streams down the steep ramparts of the Sierra, flowing into two regional rivers joining in a vast delta, opening out the Golden Gate to the sea. This dry, but lush, land enjoys a sunny Mediterranean climate on the mid-Pacific Coast.

This bioregion was home to about thirty-seven million people in 2009, forming one of the greatest economies on earth. The two great megalopoli of the L.A. Basin and the Bay Area dwarf the cities of Cascadia. This bioregion was home to about thirty-seven million people in 2009, forming one of the greatest economies on earth. The two great megalopoli of the L.A. Basin and the Bay Area dwarf the cities of Cascadia.

The flows of goods and people back and forth between California and Cascadia are enormous, of course, as are the continuous exchanges of information, services, money, etc. However, two commodities always seem to flow south in California’s favor—water and energy. Southern California has long lusted after the abundant waters which define Cascadia, and hatched elaborate schemes to siphon our living waters south. Remembering the adage that “in the west water doesn’t flow downhill--it flows toward money,” future generations here will need to remain vigilant against the dangers of so-called “inter-basin transfers.”

Tapping the wide-reaching resources of its “aqueduct empire,” this arid land blooms a great market-garden growing fruits and nuts and vegetables and milk, and a thousand other crops. Enjoying a temperate year-round climate, California is the largest agricultural producer in the country. It’s a purveyor of fine wine, digital devices, and movie dreams to the world.

California seems familiar to us all, but it constitutes a complex world all its own on many levels. So powerful is this complex that California is taking the leap beyond bioregion and culture to a separate “civilization.” As such, it invites its own fuller treatment elsewhere.

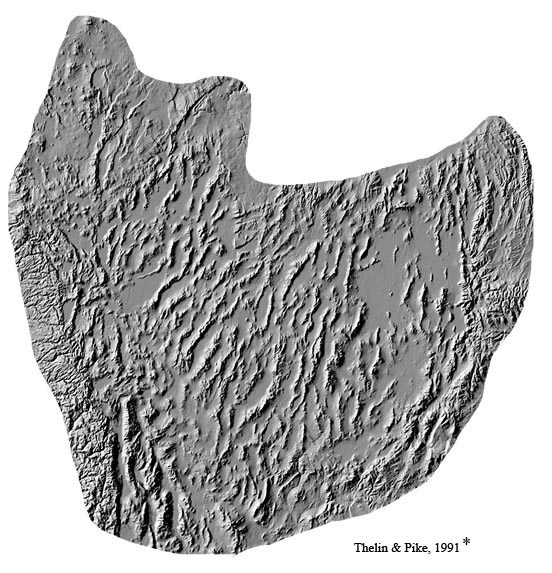

The Great Basin

On California’s east side stands the vast fault-blocked landscape of the Great Basin and Range province. Stretching from the wall of the Sierra Nevada on the west, all the way over to the Wasatch range of Utah on the east, the mountains in between rise as a series of north/south trending ranges, looking like “an army of caterpillars crawling north,” in one famous description.

Geologists say that the region is a “pull-apart” basin--one that is being arched up from underneath and stretched from both sides--opening cracks all the way down through the middle. As the earth’s crust slivers along these tensions or fault-lines, one block of rock falls down as a whole, forming a basin, leaving an adjacent block standing higher. This squared-off fault-blocked basin reaches all the way up into central Oregon through the gate of Paulina Peak/Newberry Volcano (which may soon be tapped for geothermal energy).

This world presents a rectangular landscape different from the curving arcs of Cascadia. Like sections of the “eastside” of Cascadia, the Great Basin is dry, a cool desert steppe most of the year, standing in the deep rainshadow of the high Sierras. Here, again, the drier the leeside, the steeper the windward side, and the Sierras are very steep, indeed. Close proximity enables many Great Basin “xeric” or dry species to migrate north into the interior volcanic plateaus mentioned earlier, such as western Juniper.

In many ways, the Great Basin has its own stark, stunning power and beauty, though far fewer people live there than in California or Cascadia.

Indeed, the Great Basin has always been sparsely populated, whether in its Paiute Indian or modern incarnations. This region was part of “The Great American Desert,” and largely skipped over in the Westward migrations toward the Willamette Valley of Oregon and the Bay Area of California. Today, its cities are suspended in the tension between “saints and sinners” in the desert (the sacred temple of Salt Lake City, on the one hand, vs. the gambling centers of Las Vegas and Reno, on the other hand).

The Mormon dream of a Great Basin “Kingdom of Deseret” lives on in its far-flung settlements radiating out into the farming communities of Idaho’s Snake River Plain, as well as throughout Utah, and the desert Southwest.

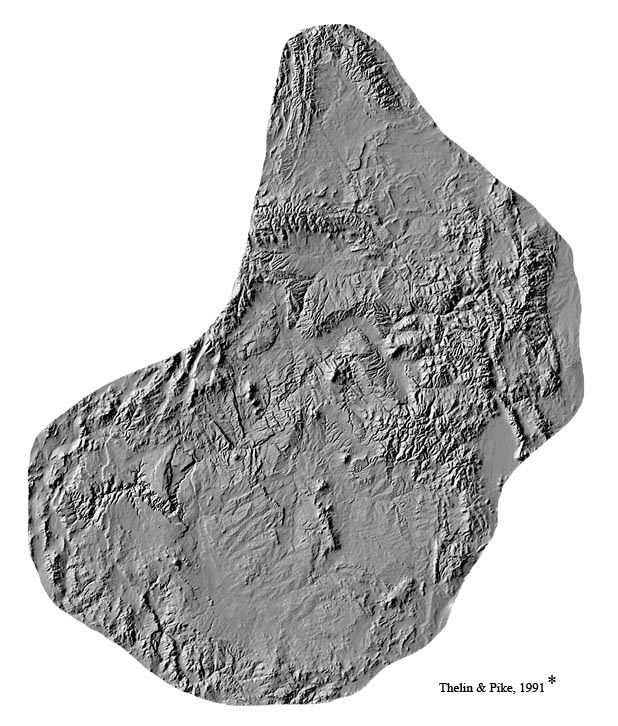

Colorado Plateau

On the eastern shoulder of the Great Basin, and on the southeastern border of Cascadia, but still west of the Great Divide, stand the high red rocks of the Colorado Plateau. You pass through the Yellowstone gate into the Green River drainage, rising from the beautiful high Wind River Range in Wyoming, and curling down through Colorado.

This plateau was once part of a series of great seas flooding the interior of the North American continent. Here tens of thousands of feet of vast belts of sedimentary rocks were cemented together over geologic time. Sandstones, limestones, shales, and more sandstones of every imaginable hue ranging from gray and pink to orange and red to creamy-white, still stand in the undisturbed sequence in which they were laid down on the floors of those ancient, steamy seas. Its hard to believe but true that this whole body of rock was lifted upwards as a single block over one and a half miles into the sky.

Because these old sediments were lifted as a huge, single, unbroken block of rock, and held intact in between the Wasatch Range to the west, the Wind River and Uintah Ranges to the north, and the magnificent Colorado Range to the east, as well as the venerable Sangre de Cristo Mountains to the south, this great raised plateau received enormous rain and runoff through geologic time.

Water is one of the great gods of this region, and powerful seasonal pulses, especially flash floods from summer thunderstorms, deeply incise the great layered plate, cutting down into the bedrock of the continent, down into the underworld itself seen in the Vishnu schist at the bottom of the Grand Canyon of the Colorado River.

In many ways, Cascadia and the Colorado Plateau stand forth as opposites. In Cascadia, for instance, the landscape is clothed in vegetation, while in the Colorado Plateau everything stands burnt naked and open as the bare rocks. In Cascadia, topographic density is so great its sometimes hard to spot the horizon, except on ridgelines or over open water, while in the Plateau everything is horizon all the time in every direction.

The light is different, and weather, too. In Cascadia, due to the close embrace of the ocean and moisture-suffused atmosphere, a filmy light tends to envelop everything in a kind of gauzy, gray-green, luminous numinosity. In Seattle, they call it “oyster light,” while further north in Alaska, people dwell in wintertime in “the dreamlight.”

In the chromageography of regions beloved by painters and photographers, Cascadia is gray and green with a tan undertone, while Colorado is red-orange to brown. Cascadia is water-colors, the Plateau oils.

In the Colorado Plateau, there’s a special hard-edged crystalline clarity to the light. There’s a kind of breathless, brilliant, almost brittle light with a blue undertone breaking over the horizon in the morning, relentlessly bathing everything in its white, harsh, shadowless, radiance. In summertime, the sun bores right through you, metal burns and rocks hum. This overwhelming bath of radiance is relieved in summertime only by the wild prophetic thunderstorms crashing on this high island shore.

Weather is different, too. The Colorado Plateau receives its moisture boiling up from the over-heated Gulf of Mexico, creating a summer-time monsoonal pattern with epic lightning and thunderstorms. Lightning and water are the great gods of this place, while Cascadia has fewer thunderstorms than almost any other place in the country. The seasons are reversed—while Cascadia is winter-wet and summer-dry, the Plateau is winter-dry and summer-wetter.

Then, too, the Colorado Plateau presents a horizontal world with an infinite horizon and far-view, while Cascadia presents a vertical landscape. On the Plateau, you’re riding a flat high island floating in the sky, and this creates what might be called from a Cascadian perspective an “inverted landscape.”

Coming from Cascadia, you’re accustomed to climbing high above treeline to gaze back down over the valleys below, working hard to catch a wider glimpse of the land you love. But in the high Southwest deserts, roaming free on the mesa tops, you can already see forever. It’s an endless, encircling, immediately present horizon affording the far-view.

While in Cascadia you climb up into the sky to touch the horizon, on the Plateau you climb off the exposed expanse of tablelands down into the canyon country below, seeking the oasis-like sheltered shadow of the cliffs, out of the harsh irradiating bath of light, and the gritty, scouring wind.

In fact, it is these cliffsides, openings, and folds, in the earth that pre-EuroAmerican peoples sought out from Mesa Verde on the east all the way over to Hells Canyon on the west. For the canyonlands offered the only real niche or invitation to dwell in these parts. Winter meant staying down in the warmer canyon bottoms, telling sacred stories and husbanding the tribe, catching southern light in the cupped bowl of the cliffs. Summertime meant roaming free up in the cool mountains. Spring and Fall were spent on the verdant plateaus and golden mesas, hunting, gathering, and occasionally raising crops by capturing water.

In a number of ways, then, Cascadia and the Colorado Plateau stand out as polar opposites, Northwest and Southwest constituting axial landscapes of North America.

Since we all tend to take our own familiar worlds for granted, as natural and equivalent to the whole world, the best way to understand your world is to leave it, to “gain perspective by contrast.” Sometimes you only understand things in reverse—by what they are not—and the polarities of Southwest and Northwest serve as a case in point.

In addition to the other contrasts of dry and wet, bare and clothed, red and green, horizontal and vertical, canyonlands and peaks, summer and winter, you find in the high desert that “Sky Determines All,” while in Cascadia, “the Sea Gives Birth to Everything.” The Colorado Plateau is old, bleached bones, Cascadia new, green forests, one is lizard sunning, the other salmon leaping; and these polarities continue to ramify through the whole of life.

In short, if you would come to realize what Cascadia means, get to know the Colorado Plateau!

More sparsely populated than even the Great Basin next door, there are no great cities on the Plateau. In fact, there are no cities at all larger than 100,000 population, and only a handful 20,000 or above (the widely dispersed towns of St. George & Cedar City, Utah, Flagstaff, Arizona, Grand Junction, Colorado, Farmington & Gallup, New Mexico, with Rock Springs, Wyoming, bringing up the rear).

But there remains, of course, a vibrant First Nation’s peoples’ presence—the Hopi and Navaho, along with Pueblo peoples next door—centered on the Four Corners area.

In short, the Colorado Plateau is surely a very different country than surrounding bioregions, and constitutes the reversible pole of Cascadia. Indeed, the country as well as the world share an eternal fascination with this land so different than anything else on the continent. It exudes its own special spirit of place….

In sum, California is our neighbor, a golden haired lover. We both hug the coast, but in different ways. The Great Basin is also our neighbor, though we may not visit as much. But the Colorado Plateau is our true opposite, and as “opposites attract,” together we form a prime polarity of axial landscapes.

* Digital Shaded Relief Maps Courtesy of U.S.G.S., Gail P. Thelin & Richard J. Pike, 1991, Landforms of the Conterminous United States; note images here are not to same scale.

Other Surrounding Bioregions

In terms of the larger continental context, there is not room here to explore here the vast landscapes on the other side of the Great Divide. For now we can only mention them.

To the north and east of the Colorado Plateau, stand the “high, wide, and lonesome,” High Plains. Rising from the roof of Yellowstone, the bioregion of “Missouriana” ramps down from the Rockies through eastern Montana into Nebraska through vast grasslands, once roamed and formed by a 100,000,000 buffalo.

North of Missouriana stand the northern prairies of Saskatchewan and Alberta.

North of the Saskatchewan and Athabasca bioregions flows the Peace River bioregion, bordering and then entering the vast, somber belts of boreal spruce forest.

North of the Peace flows the huge and powerful Liard-Mackenzie bioregion rolling through mountains, boreal forest, and taiga, to the Arctic Ocean.

Northwest of the Liard rises the Yukon, flowing from the same Kluane-Wrangell-St. Elias raft of ranges that feed the Alsek-Tatshenshini river draining south into Cascadia.

And west/northwest of the Yukon bioregion stands the great land, Alaska, another world unto itself.

In its external contexts, then, Cascadia is located as the land north of California and the Great Basin, northwest of the Colorado Plateau, west/northwest of Missouriana, west of Saskatchewan and the Peace, southwest of the Liard and Yukon, and east/southeast of Alaska. These are the contiguous bioregional neighbors of Cascadia, proceeding counter-clockwise.

In terms of population, it is astounding how empty the millions of square miles surrounding Cascadia remain. For instance, there is not one city over a million people. Only two cities are larger than 700,000 people, and they’re both in Alberta, Canada—namely, Calgary and Edmonton. There are only three more cities over 100,000 people—Anchorage, Alaska, and Saskatoon and Regina, Saskatchewan. This belt of surrounding bioregions is surely one of the least populated areas on earth.

Indeed, outside of California and the Las Vegas-Reno-Salt Lake City areas, there are only five major metro areas in the wider swath surrounding Cascadia—namely, Phoenix, Albuquerque, Denver, Calgary and Edmonton. The paucity of population in this vast Empty Quarter makes the metroplex corridor of Greater Portland, Seattle, and Vancouver, B.C., even more significant.

Of course, what looks like “emptiness” from a human demographic and economic point of view, is not empty at all, but rather “full” from an ecological perspective, as a refuge for wildlife and biodiversity, etc.

Cascadia’s Role in North America

Finally, let us consider Cascadia in the context of all of North America. As John Muir said, “Mountains are the fountains of the waters,” and nowhere is this more true than in Cascadia.

Cascadia, of course, springs forth many great rivers down its own slopes, and these rivers flowing into the basins of the Cascadia Sea play a unique role in the marine ecology of the northeastern Pacific Ocean.

At the same time, it is little known that she also sends sweet green waters down the other side in all directions. For Cascadia is the prime source or major contributor to many of the great river systems of the continent, such as the Sacramento and Humboldt on her southern slopes, the Missouri-Yellowstone, Saskatchewan, and Athabasca, on her eastern slopes, and the Peace, Liard, and Mackenzie, on her northeastern slopes, as well as the Yukon and Copper Rivers on her northwestern slopes.

The Pacific, Arctic, and Atlantic, oceans are linked by this very special regional flow over the crest of the continent, which plays an important role in the ecology of the entire northern hemisphere.

back to where you were reading

home page

|

|