These days latitude and longitude coordinates even show up on mobile phones, and suddenly, it seems magical to “know exactly where you are in the world.” But where is that? What does 125° by 45° tell you? What are you going to do with that data? Without a map to navigate, the lone point dissolves into thin air, and certitude vanishes when one discovers that, literally, “there is no there, there.”

(Point position is meaningful only within a framework, and any grid system needs to be “geo-referenced,” that is, brought down to earth and tied to the actual terrain. So start with the terrain, because that’s where you’ll end up anyway. It’s the difference between trying to live in an abstraction vs. putting down roots in a place. In an old phrase, “the map is not the territory”).

In a number of ways, we seem confused about location and orientation today. Standard geographies substitute isolation for location, when isolation is actually the opposite of location. GPS chips are now embedded in digital technology everywhere, but may be dis-orienting rather than orienting us. Over-reliance on the new technology, for instance, and computer voices giving directions, “turn here, turn there,” removes us from attending directly to the place itself, and learning the lay of the land, sometimes with tragic consequences.

Such confusion invites clarification. A pin-point position in an abstract grid, for instance, is not location. Part of the problem is that Cascadia is found not on a globe but in the earth. While position on a grid in the sky offers a god’s eye view from space, location is not a number, but a process of finding our way inside the place.

The readout which provides latitude/longitude coordinates, after all, is only good on a map, and a map provides an image of the world. A map is a scaled-down representation of the structure of the world. To find your way with a map through the world, you have to be inside that world and an image of that world must be inside your head as well, else you can’t “read” the map or the world. The readout which provides latitude/longitude coordinates, after all, is only good on a map, and a map provides an image of the world. A map is a scaled-down representation of the structure of the world. To find your way with a map through the world, you have to be inside that world and an image of that world must be inside your head as well, else you can’t “read” the map or the world.

And the only way this image of how the world is organized gets in your head is if its first in your body, while moving through the body of the world. The first map is a lived image of the body of the world. Location is the embodying of these relationships. True location is not found on a map but in the process of finding your way in & through this world.

Location as a Process

“To locate” is “to place,” the act of composing a place. Location and place, then, are intimately intertwined.

On one level, to locate means to place something in a meaningful relationship, to orient to one’s surroundings, and to find direction to a desired place.

Thus, location as “placement” means not just to determine position, but discover “what’s going on there,” the locus of daily and extraordinary activities.

Location as “orientation” means to “find our bearings,” to position ourselves in relation to the directions (how things flow), so as to align our body with the structure of the world. Through this deeper orientation we gain “perspective,” composing a view enabling us to “see- through-from-here-to-there.”

And these insights lead to location as “contiguity,” which means that we discover how things are in contact, how “what’s next to what” and “what’s over there” or “on the other side,” fit together, one to the other. We seek to comprehend the integrity of the earth’s body, how “the hip bone is connected to the thigh bone,” and so on. This enables us to compose an image of the place as a whole.

Building on these perspectives, we shift to a deeper level of location when we move from “journeying to dwelling,” that is from “way-finding” to “finding a place for dwelling.”

Location, then, means to situate ourselves within the life of the place, to settle into a dwelling place, to take up residence or establish domicile, to find a home for the full round of life.

Here locus is focus--finding the path of converging rays leading to the hearth as the gathering center of a house and home, leading into the heart of things.

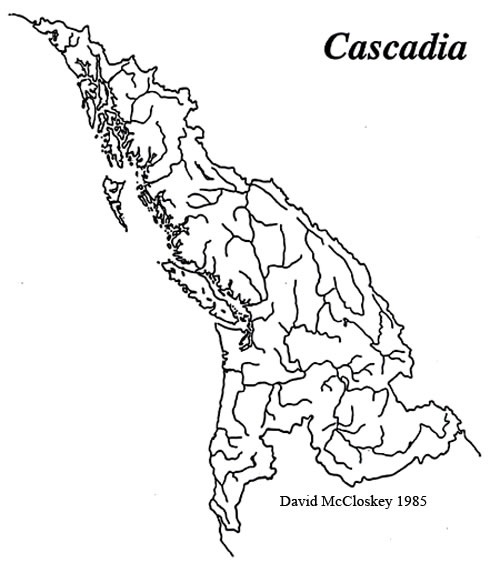

Cascadia’s Location

Where, then, shall we find Cascadia? What shall we look for?

Remember its not a matter of spatial position on a grid nor distance away, but rather what’s happening here, and our relationships within this field of forces. In trying to discover its deeper locations, let us return to the initial insight of Cascadia as “two directions converging in one place.”

This region acts as a threshold, joining different worlds together. Cascadia is a meeting ground between land and sea, east and west, north and south, between ancient and modern cultures, Canadian and American societies, between Euro-descendants and First Nations peoples, and all these dimensions working within an emerging pan-Pacific Rim culture.

To articulate the intrinsic location of Cascadia, we need to enter into these dynamisms. For Cascadia takes up its location primarily as a threshold or “crossing-over-and back place.”

In physical terms, for instance, Cascadia is located where mountains meet the sea. On this great long curving crennelated coastline, the sea caresses land with wild winds and waters, spinning in endless streaming gyres. From this embrace, rivers in the sea raise rivers in the sky, and rivers in the sky fall and nourish rivers in the land, and rivers in the land stream down to feed the sea in turn.

Cascadia is a locus of these round turnings, a hinge or pivot moving both ways inside the living body of earth-sea-sky. Like a sail curving into the wind, Cascadia stands forth as a leading edge, a convergent threshold poised “on the verge” of a vast field of forces.

Location, then, involves discovery of the dynamism of how this particular “world turns.” Location means articulation of relationships of parts to wholes to form a field of significance.

When we seek to articulate the location of Cascadia in these deeper dynamic senses, we hope to discover her character & context.

“Character” describes this body from inside the region—the face of the place, its lineation or lay of the land, its dynamisms, and how it works as a gathering place in a field of forces.

“Context” describes the region from the outside—how inside and outside dimensions weave together with other regions in the larger body of the earth.

back to where you were reading

home page

|